My own writing comes out of two distinctly different literary traditions: fantasy and noir. Of the latter, I claim red-headed-stepchild kinship with both the classic (Chandler and Hammett) and the modern (Robert B. Parker) in my Eddie LaCrosse novels.

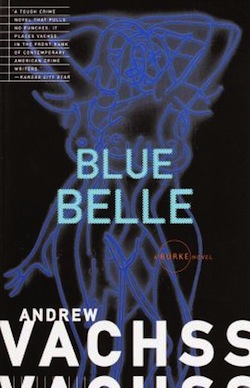

But a deeper influence, and one of my favorite living authors, Andrew Vachss, caught me with a single sentence, the first line of his third novel, 1988’s Blue Belle:

“Spring comes hard down here.”

I’ve never met Vachss, although we both have book-related t-shirts available through Novel-Tees (all proceeds go to PROTECT, an organization that lobbies for stronger child-protection laws). He first came to my attention via a review I read in a waiting room magazine. It talked about Blue Belle‘s relentless sex (which isn’t really true), as well as the fun of watching the hard guy (Vachss’s hero, Burke) melt. This also isn’t really true, because Burke is always melted, and always a hard guy; it’s one of the contradictions that makes him compelling.

Shortly thereafter, at a cavernous Books-A-Million, I came across Vachss’s first Burke novel, Flood. I found it wonderful despite some first-novel issues that Vachss himself subsequently acknowledged (“I expected Flood to be my one chance in the ring,” he told interviewer Ken Bruen, “which is why it is so long: I threw every punch I could in the first round.”). What really jumped out was not the revenge plot, but the “family of choice” that Burke, on the surface the quintessential loner, built around himself. In later books (the series concluded in 2008 with Another Life), this family became more and more central, more integrated with the plots and with Burke himself.

While I enjoyed Flood and the second novel, Strega, I discovered in Blue Belle a new sensitivity and sensibility that spoke volumes to me. Vachss had been good before, but here he seemed to hit the next level. Again, it wasn’t the plot: it was the way these damaged but determined people related to each other, the edgy dance of Burke and Belle as they found their common emotional ground.

And that opening line: “Spring comes hard down here.” In five words he sets a scene as vivid and alive as any endless, adjective-dripping paragraph. You sense the quality of the light, the bite of still-lingering chill, the fresh promise of warmth all mingling with the shadows of old gigantic buildings and the smell of exhaust. It’s the work of a magician casting a spell, pulling us through a rusted-metal wardrobe into his own Narnia where life is cheap, but love (and not just romantic, but also family-of-choice affection) is priceless.

Blue Belle, and Vachss in general, aren’t as obvious an influence on my writing as Chandler, Hammett and Parker. But that book awoke an awareness in me that had not been there before, and without it, the Eddie LaCrosse novels wouldn’t be the books they are. Which is why the first line of The Sword-Edged Blonde (“Spring came down hard that year”) is both a play on, and a tribute to, Vachss and Blue Belle.

Alex Bledsoe is author of the Eddie LaCrosse novels (The Sword-Edged Blonde, Burn Me Deadly, Dark Jenny, Wake of the Bloody Angel), the novels of the Memphis vampires (Blood Groove and The Girls with Games of Blood) and the Tufa novels(The Hum and the Shiver, and Wisp of a Thing).